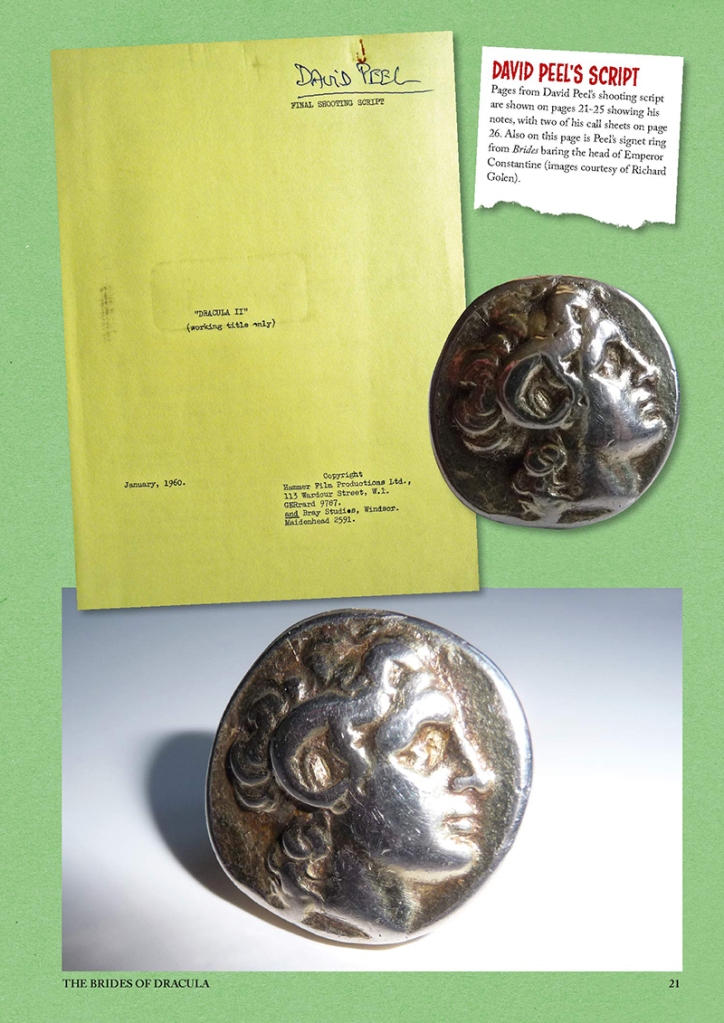

This week I ordered a copy of The Hammer Vampire Scrapbook by Wayne Kinsey. It hasn’t arrived yet, but I’m already fascinated by this page (one of a dozen made available as previews on the Peveril Publishing website, and which I hope they therefore won’t mind me replicating):

It shows the signet ring David Peel wore as the Baron Meinster in The Brides of Dracula (1960): something I’d never previously noticed when watching the film. Checking back, I could see why. It isn’t very prominent. However, Peel certainly is wearing a signet ring in the film, and after revisiting it and some of its publicity materials, I’m pretty convinced it is indeed the one shown in Kinsey’s book.

The signet part of the ring seems to be an ancient coin. Although the pictures in Kinsey’s book don’t show the back, presumably at some point the ancient coin was welded onto a modern ring so that it could be worn, and in the bottom of the two images it seems to be standing propped up on that ring.

But the image on the ring isn’t the Emperor Constantine, as Kinsey has it. It is most definitely Alexander the Great. If you need convincing on that point, here’s a page of the coinage of Constantine, and here’s an equivalent for Alexander the Great. They lived 600 years apart, and it’s not just that their portraiture is different: their coinage is technically and stylistically extremely different too.

I’m not saying this purely to be pedantic. I’m saying it because I think knowing that David Peel wore an Alexander the Great signet ring to play the Baron Meinster adds at least two, possibly three, extra little windows of insight into Brides of Dracula as a film.

1. The Queer

Recently, I took part in a livestreamed webcast with notorious Hammer-enablers and all round lovely fellows Hammer Gothic and exclusivephd. We talked our way through the first three of Hammer’s vampire films, including Brides, and very much agreed that all three are absolutely dripping with queer subtext. There is a long-standing tradition in both literature and film of vampires being coded as both queer and gender-transgressive anyway, while a large part of Hammer’s approach to vampirism was to treat it more or less directly as a metaphor for sex, inviting those themes ever closer to the surface.

In Brides specifically, the queer coding around the Baron Meinster includes the way his mother keeps him out of the public eye and talks about how she is ashamed of his lifestyle, and the final confrontation between him and Van Helsing, in which the Baron swings a chain at his opponent, chokes him and then bites him. After the bite, we get a close-up view of the Baron’s face with Van Helsing’s blood dripping down his chin, followed by a cut to Van Helsing, his face beaded with sweat, his clothes askew, and the open wound on his neck oozing with those same bodily fluids. I am just telling you what’s there on the screen.

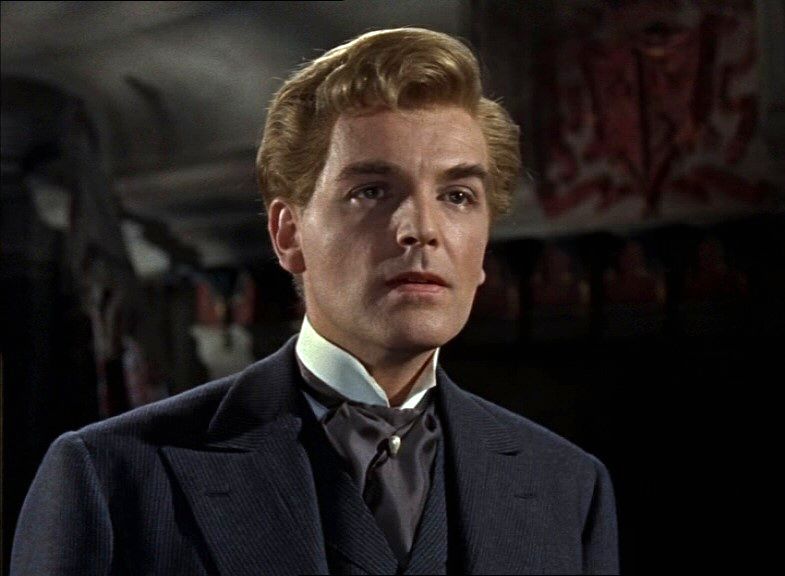

It’s possible that some of this came to the fore within the narrative because David Peel, who played the Baron, was gay: at least as far as we can reliably say for someone who died in 1981 and couldn’t have been publicly out in 1960. Certainly, although there are ways in which Christopher Lee’s Dracula is also queer-coded and gender-transgressive, we never see his character biting another man on screen. Perhaps Peel was willing to play up those angles in ways that Lee wasn’t, or other members of the production team found them easier to imagine?

Back to the Alexander the Great signet ring. Alexander’s sexuality is even harder to pin down in modern terms than Peel’s. He lived in a time when there was no real concept of a person’s sexual identity, and the sources for him are highly mythologising anyway. But he is widely regarded as a queer icon. Here’s just one rather good blog post on the topic.

In that light, knowing that in Brides the Baron Meinster wears an Alexander the Great signet ring definitely adds to his queer coding. In fact, I wonder if that little touch came from Peel himself. Wikipedia tells me that when he moved out of acting only a few months after completing Brides of Dracula, one of the alternative careers he pursued was in antiques dealing. If he had that interest and those contacts already when making Brides, it might explain why he had such a ring or understood its historical resonances. Perhaps in fact it was simply a ring he wore regularly himself as a veiled way of expressing his sexuality? I’d love to know.

2. The Pagan

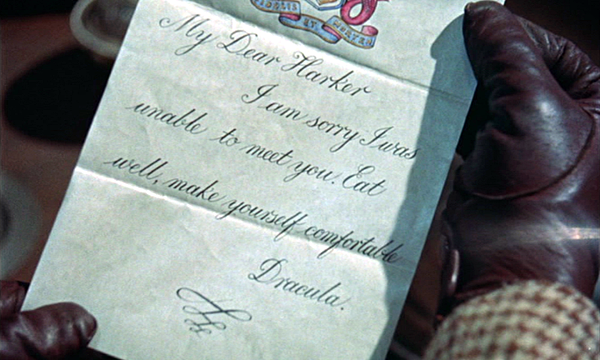

Another aspect of Brides of Dracula which I’ve always loved is the way it casts vampirism specifically as a pagan cult. At one point, Van Helsing explains to the local priest, Father Stepnik, that vampirism is ‘a survival of one of the ancient pagan religions in their struggle against Christianity’. This doesn’t come out of nowhere. Stoker’s novel contains references to pagan deities such as Morpheus and Demeter, and at one point when things are going badly with Lucy, Van Helsing exclaims: ‘Is there fate amongst us still, sent down from the pagan world of old, that such things must be, and in such way?’ The zodiac wheel on the library floor in Dracula (1958) is also inscribed with some distinctly pagan texts. But Brides states it outright as an explicit part of the equation.

Again, Alexander the Great adds to this. He lived in a pagan world, but more than that the specific image of him shown on the Baron’s signet ring reflects the ways in which he used religion to enhance his position as a ruler. It shows him in a divine guise, his head adorned with the horns of Zeus Ammon, whose priests hailed Alexander as his son when he visited Ammon’s sanctuary in Egypt. Alexander seems to have encouraged this belief in life, but the coin used for the Baron’s signet ring in Brides is actually a type widely minted by Lysimachos, who became king of Thrace after Alexander’s death. Here’s a typical example. By the time Lysimachos was minting those coins, Alexander was being treated posthumously as the object of religious cult in his own right, so the coin shows a chain of divine descent: Lysimachos’ patron deity, Alexander, with horns indicating his own connection to Zeus Ammon.

Going back to Brides, there are all sorts of things we can do with this. Was the pagan religion Van Helsing referred to the cult of Zeus Ammon? Or perhaps of Alexander himself? Perhaps the Baron is like Lysimachos: an aristocratic ruler drawing his power partly from association with the patron deity whose image he bears on his signet ring? Again, not to be pedantic, these possibilities aren’t available for consideration if we think the signet ring bears the image of Constantine. Indeed, it would make absolutely zero sense for a vampire in the Hammer-verse to be wearing the image of a Christian emperor.

3. The Hair?

The third aspect I’m not so sure about, but I’ll put the idea out there anyway. In Brides of Dracula, David Peel sports not his own natural dark hair, which can be seen here, but a blond costume wig with a sort of curled quiff at the front. In keeping with a trope already established in Dracula (1958), we see this in two guises: neatly ordered when he is engaged in passing as human for nefarious purposes, and tousled when his bestial vampiric nature comes to the fore.

Peel’s hair in this film is normally discussed in terms of appealing to the teen market by presenting him as youthful and charming, but as it happens, Alexander the Great was also blond, and his portraiture showed him with tousled hair and curls breaking over his forehead.

We don’t need to believe that anyone in the Hammer make-up and wardrobe department was familiar with the ancient portraiture of Alexander the Great to draw a link between the two, because there had been a recent intermediary. Richard Burton’s title character in Alexander the Great (1956) also sports curly, tousled hair in a very similar strawberry-blond shade to the Baron Meinster’s.

The styling isn’t quite the same, of course, which is why I’m not sure I really want to commit to this one. But it’s just possible that the Baron Meinster’s curly fringe and tousled vampire-mode hair were designed as another way of evoking Alexander the Great: specifically as portrayed in the 1956 film.

I’d love to be able to close the loop at this point by saying that such a connection also feeds back into the Baron’s queer-coding, but there things definitely fall apart because Richard Burton’s Alexander is thoroughly straightwashed. But it doesn’t really matter. We have an image of the real Alexander on the signet ring right there in the film, and that’s enough for me.